From the Great War to Agricultural Landscapes: Achille Beltrame and the Anonima Grandine Calendars

11 January 2024

A sensitive examiner when it came to human feats, and a clear-eyed portraitist of the foul deeds of war in the early- and mid-1900s, Achille Beltrame (Arzignano di Vicenza 1871 – Milan 1945) had a talent for rendering the story of Italian society and customs into a language that was colourful yet understated, accurate but without descending into harsh realism. In doing so, he ensured the general public was informed and up to date on national and global events.

Despite being an astute interpreter of reality, Beltrame never left Milan, after moving there in 1886 to attend courses at the Brera Academy, where he initially stood out first and foremost as a painter of mural panels and paintings of religious and historic scenes.

The name and reputation of the artist from Arzignano remain intrinsically linked to his years-long work as an illustrator for the popular weekly newspaper, La Domenica del Corriere, from 1899 onwards.

An exceptional communicator and a storyteller ahead of his time, his works were based on reports by correspondents and made use of a personal photography archive.

He was also dedicated to designing posters and advertising graphics, collaborating with leading graphic design studios of the early 1900s such as Alfieri and Lacroix, Modiano, and the Milan-based Officine Grafiche Ricordi: his most famous works are those he did for Mele, the famous department store in Naples.

Between the First World War and the early 1940s, he was entrusted with almost all the almanacs (illustrated calendars) for Anonima Grandine, the Generali subsidiary founded in 1890. Generali first entered the rapidly expanding hail insurance sector all the way back in 1836, with the first Italian insurance policy against hailstone-related damage, the brainchild of then-secretary general Masino Levi.

Important for the categorisation of Beltrame’s graphic-illustrative works, including the sketches for Anonima Grandine’s calendars, is the original notebook in which the artist jotted down, year after year, his works, their titles, the clients, and the sum he received for them. This notebook has now been transcribed and reproduced by Franco Barbieri and Annalisa Cera (eds.) in Achille Beltrame (1871-1945). La sapienza del comunicare: illustrare con la pittura, Milan, Electa, 1996. This source provides a list of 16 works that acted as “rough drafts” for almanacs commissioned by Anonima Grandine.

The projects are listed as “sketch” or “painting”, with only a title, and here and there also the painting technique. They are never defined as “almanacs”, although they can be identified by the data, commissioning client (the aforementioned Anonima Grandine) and in a few cases also by the subject in oil and watercolour, as well as a few related calendars that form part of Generali’s heritage.

Included in Generali’s artistic heritage are the paintings for the calendars from 1916-1920 (four samples out of five identified, oil on canvas, with the only exception of 1916 of which the corresponding almanac is preserved) and the paintings for the calendars of 1922-1923, 1925-1929, 1931-1932 and 1941-1942 (nine pieces out of 11 identified, all oil on canvas with the exception of 1942: without any indication of the title/subject it has not been possible to identify it) and the 1929 almanac.

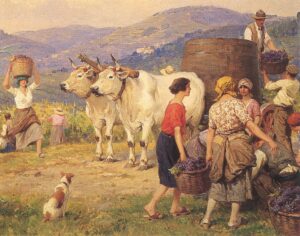

The paintings from the initial series are dominated by references to the war, tempered by the idyllic and peaceful atmosphere of the villages and farmers, while the second series is dedicated in its entirety to the rural environment and various agricultural activities.

Based on the chronology in Beltrame’s own notebook, the paintings were all produced in the year preceding that of the relevant calendar edition, and at least in the case of the first series, all for Modiano. A photojournalist of feelings, a portrait painter of reality, Beltrame was able to carefully measure quantities of imagination and narrative rigour even in the works he produced for Anonima Grandine, translating them into a sharp, clean and intuitive language that was, in the words of Paola Pallottino in Achille Beltrame (1871-1945) (p.25), “made even more immediate and effective by the deliberate adoption of a series of iconographic conventions intended to emphasise and amplify the narrative”, summarising in a “single frame” a whole range of emotions and communicative gestures that are combined to describe an event.

Respectful of public sensitivity, Achille Beltrame described “an affectionate, if never simple or unhappy, daily life,” in the words of Rossana Bossaglia, in Achille Beltrame (1871-1945) (p. 11), making his mark on the posters and in small adverts for the company, which used his works on subsequent occasions. Freed from his obligations for the almanac, he was tasked with refreshing the image of the company to reflect its maternal and supportive approach as one that cared for its policyholders. One example of this is the feminine figure depicted in the painting La Raccolta dell’uva (“The Grape Harvest”) painted in 1923 that appeared on the cover of the slim volume, “Note per l’agricoltore. Viticoltura, Enologia, Canapicultura e Notizie tributarie”, as part of the “Note per l’Agricoltore” (“Farmer’s Notes”) series, full of news and practical tips for farmers, published in 1952, and that was re-used for the poster publicising Generali’s hail policy in 1992.

Respectful of public sensitivity, Achille Beltrame described “an affectionate, if never simple or unhappy, daily life,” in the words of Rossana Bossaglia, in Achille Beltrame (1871-1945) (p. 11), making his mark on the posters and in small adverts for the company, which used his works on subsequent occasions. Freed from his obligations for the almanac, he was tasked with refreshing the image of the company to reflect its maternal and supportive approach as one that cared for its policyholders. One example of this is the feminine figure depicted in the painting La Raccolta dell’uva (“The Grape Harvest”) painted in 1923 that appeared on the cover of the slim volume, “Note per l’agricoltore. Viticoltura, Enologia, Canapicultura e Notizie tributarie”, as part of the “Note per l’Agricoltore” (“Farmer’s Notes”) series, full of news and practical tips for farmers, published in 1952, and that was re-used for the poster publicising Generali’s hail policy in 1992.

For more information: Generali. Circolo aziendale (edited by), The image. The Generali Group and the art of 'advertising', Trieste, Generali. Circolo aziendale, 2010.