The Value of Oral History in Archival Research: Pietro or Riccardo Gairinger? A Case Closed

02 September 2022

Leon Battista Alberti once remarked, “Painting contains the same divine power that can be found not only in friendship, that recalls absent men, but also in bringing those deceased for many centuries back almost to life, such that with great admiration for the craftsman and with great satisfaction they may be recognised” and allows one to connect with one’s ancestors, as was the case with Dario Bartolini, the grandson of Riccardo Gairinger, whose mother was Lucia Gairinger, the daughter of Riccardo.

A Triestine by birth who lived and worked in Florence, the architect recognised his grandfather in the smartly-dressed, white-haired man depicted in Carlo Sbisà’s fresco Il lavoro costruttivo (the construction work) in the Galleria Protti in Trieste, named after Captain Arrigo Protti, a Gold Medal of Military Valour recipient who fell in combat in 1936 during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War. It is an elegant covered gallery with glass bricks above which runs the entire length of the building, based on a design by Marcello Piacentini and constructed between 1936 and 1939 on behalf of Generali.

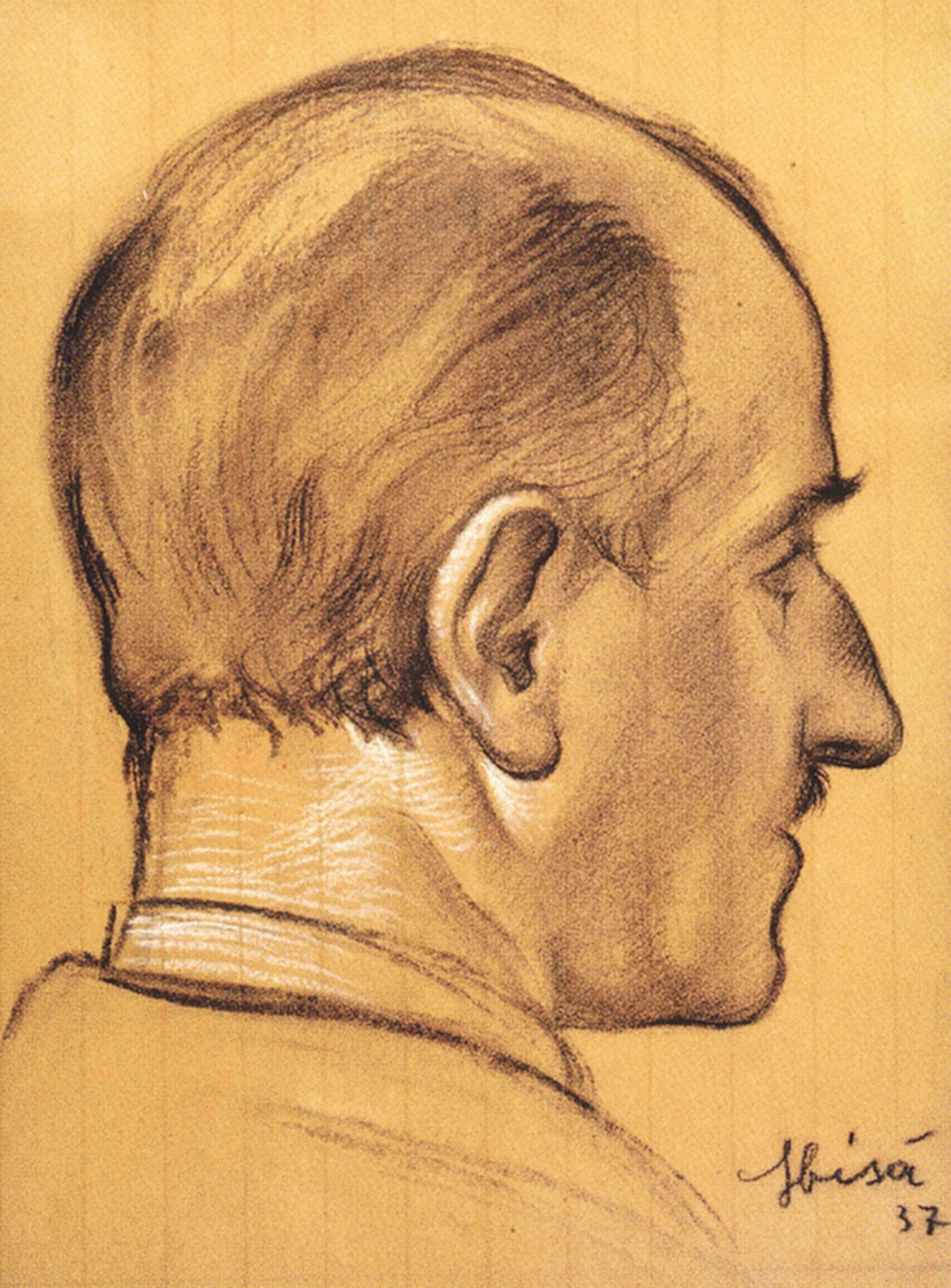

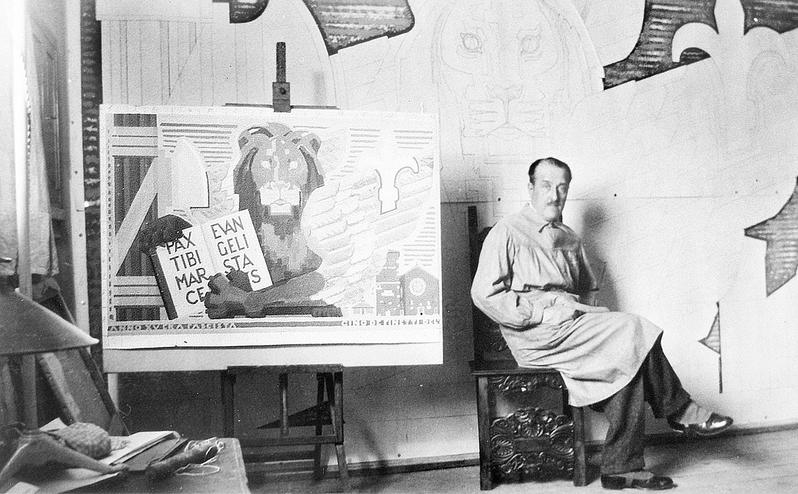

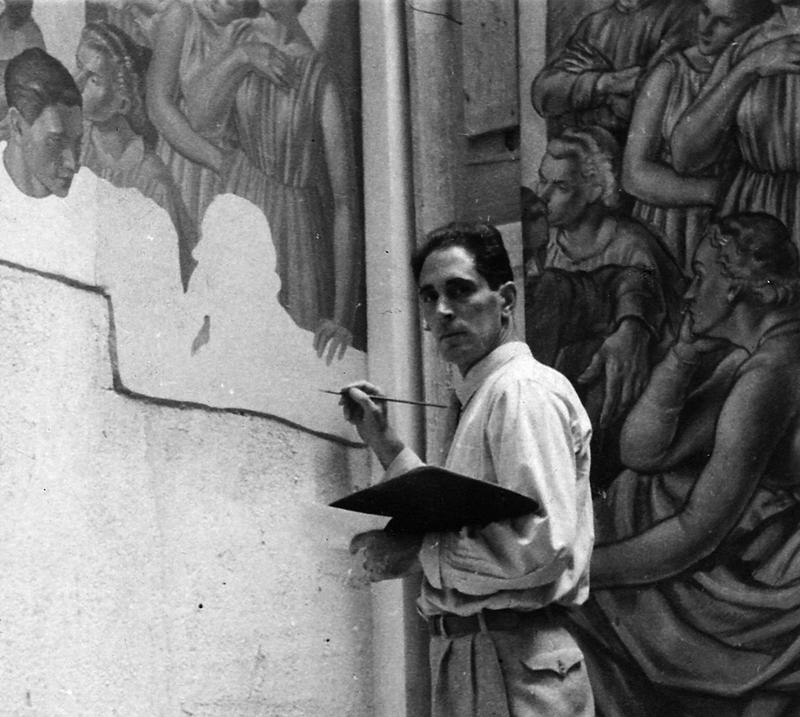

The composition depicts a group of people hard at work on a building site within a karstic landscape. There are three “familiar” faces that stand out, or who at least appear in sharp relief compared to the others – they draw the viewer’s eye, seemingly interacting with the public by turning their gaze on them. Thanks to archival and family memories, the three can now be identified: in the background, with his back to us and his head half-turned in our direction, stands Gino de Finetti, the creator of the mosaic that adorns the gallery. Gino is deep in conversation with a man wearing a jacket and tie and holding a piece of paper in his hand, who we know to be Riccardo Gairinger. Staying on the left and moving to the foreground, a young man rests his hands against the wooden scaffolding, his satisfied demeanour inviting passers-by to admire his work: perhaps this is Carlo Sbisà. An initial comparison with a contemporary photo showing the Triestine artist at work on the frescos (noting the hairline and hairstyle, the facial expression and the work attire) would seem to lend credence to this theory.

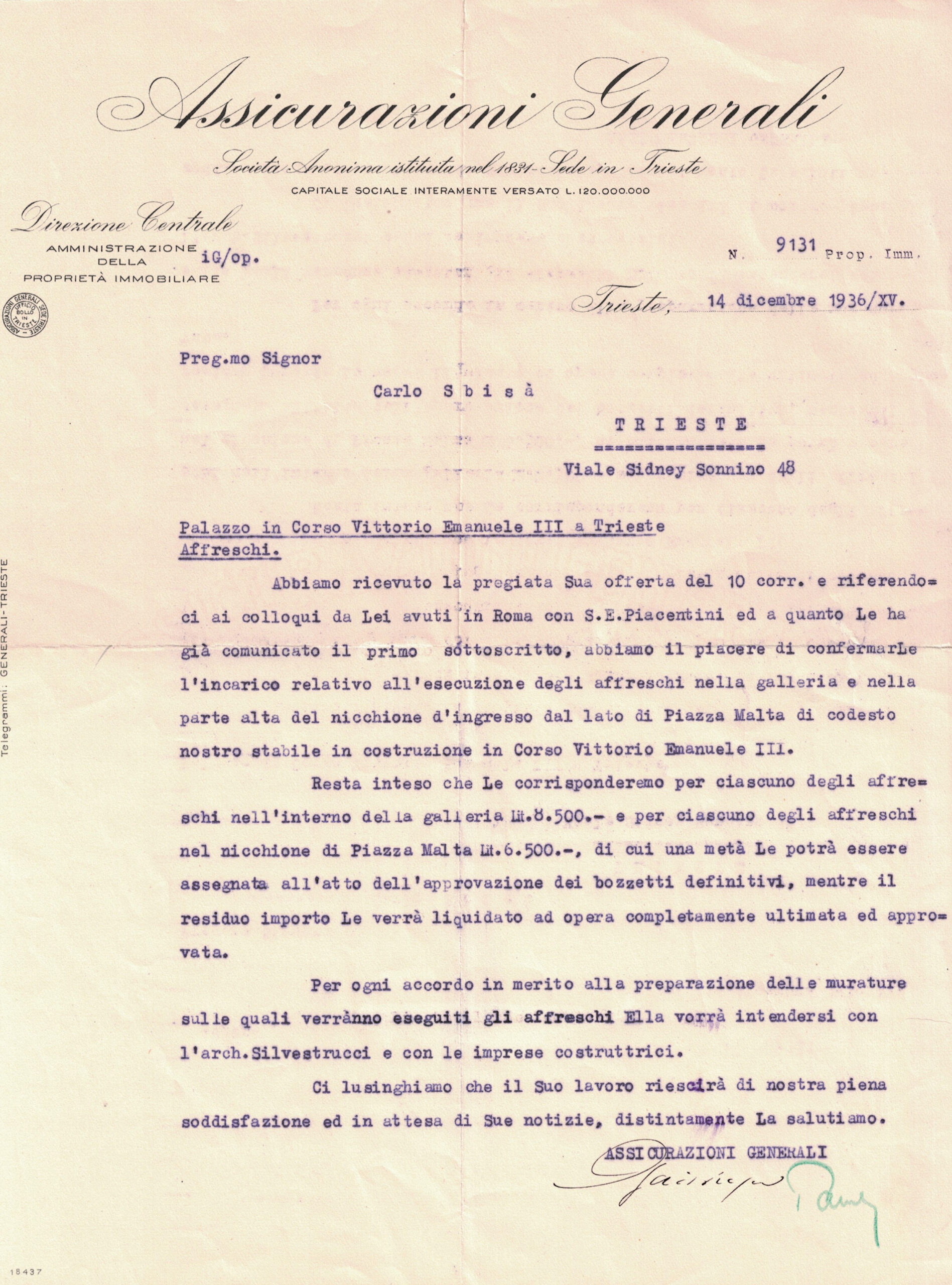

The granddaughter of Gino de Finetti, Diana Arich de Finetti, has a preliminary sketch of a portrait of her grandfather, also by Sbisà. Of Gairinger, meanwhile, there remains the memory of a granddaughter who recalls “a regular family visit to see Grandpa Riccardo at the galleria.” At the very least, she says, “the man in the portrait bears a very strong resemblance to him,” while she also has a vague memory that, “from the few photos available, Pietro [Riccardo’s brother], didn’t have a beard.”  Indeed, there are many sources – including credible ones – that confuse the brothers, mistakenly attributing to Pietro notable works on behalf of Generali and an active part in signature Triestine construction projects such as the Corso Italia complex (formerly Corso Vittorio Emanuele III), built by Piacentini with finishing touches including Sbisà’s frescoes and de Finetti’s mosaic depicting the winged lion. Part of the reason for the confusion is likely that, aside from both brothers being engineers, Riccardo was known to sign only with his surname, preceded by an abbreviation that is interpreted as being “ing.” (from ingegnere, the Italian for “engineer”). Pietro Gairinger is often erroneously credited in the specialist literature with designing the Piacentini complex and the associated artistic commissions on behalf of Generali. The source of the confusion is a letter on Generali letterhead signed with only the surname, but which was unquestionably sent by Riccardo (the letter is preserved in the Schott-Sbisà Archive). This is confirmed by the papers in his personal file as well as management and board minutes which refer exclusively to the engineer Riccardo Gairinger and never to Pietro. And above all, there are the memories of Bruno de Finetti’s daughter, Fulvia, who is unequivocal in stating that the person in question was Riccardo. The daughter of the illustrious mathematician asserts that, “within the family we spoke often about Riccardo, a close friend of Uncle Gino de Finetti, and not at all about Pietro. If Gino received this commission, he undoubtedly owed it to his friendship with Riccardo.” Fulvia de Finetti also recalled that the two owned a shared property, and that Riccardo later purchased his friend’s share. We can therefore say with confidence: it is Riccardo Gairinger, and not Pietro, depicted in the fresco speaking with his friend Gino. Case closed.

Indeed, there are many sources – including credible ones – that confuse the brothers, mistakenly attributing to Pietro notable works on behalf of Generali and an active part in signature Triestine construction projects such as the Corso Italia complex (formerly Corso Vittorio Emanuele III), built by Piacentini with finishing touches including Sbisà’s frescoes and de Finetti’s mosaic depicting the winged lion. Part of the reason for the confusion is likely that, aside from both brothers being engineers, Riccardo was known to sign only with his surname, preceded by an abbreviation that is interpreted as being “ing.” (from ingegnere, the Italian for “engineer”). Pietro Gairinger is often erroneously credited in the specialist literature with designing the Piacentini complex and the associated artistic commissions on behalf of Generali. The source of the confusion is a letter on Generali letterhead signed with only the surname, but which was unquestionably sent by Riccardo (the letter is preserved in the Schott-Sbisà Archive). This is confirmed by the papers in his personal file as well as management and board minutes which refer exclusively to the engineer Riccardo Gairinger and never to Pietro. And above all, there are the memories of Bruno de Finetti’s daughter, Fulvia, who is unequivocal in stating that the person in question was Riccardo. The daughter of the illustrious mathematician asserts that, “within the family we spoke often about Riccardo, a close friend of Uncle Gino de Finetti, and not at all about Pietro. If Gino received this commission, he undoubtedly owed it to his friendship with Riccardo.” Fulvia de Finetti also recalled that the two owned a shared property, and that Riccardo later purchased his friend’s share. We can therefore say with confidence: it is Riccardo Gairinger, and not Pietro, depicted in the fresco speaking with his friend Gino. Case closed.