1854 – Generali Anticipates the Welfare State, a European Invention

During the nineteenth century, the industrial revolution experienced a sudden acceleration, transforming the economy and society of the time. From the middle of the century, sensitivity for people’s lives – which had to be safeguarded and protected – increased.

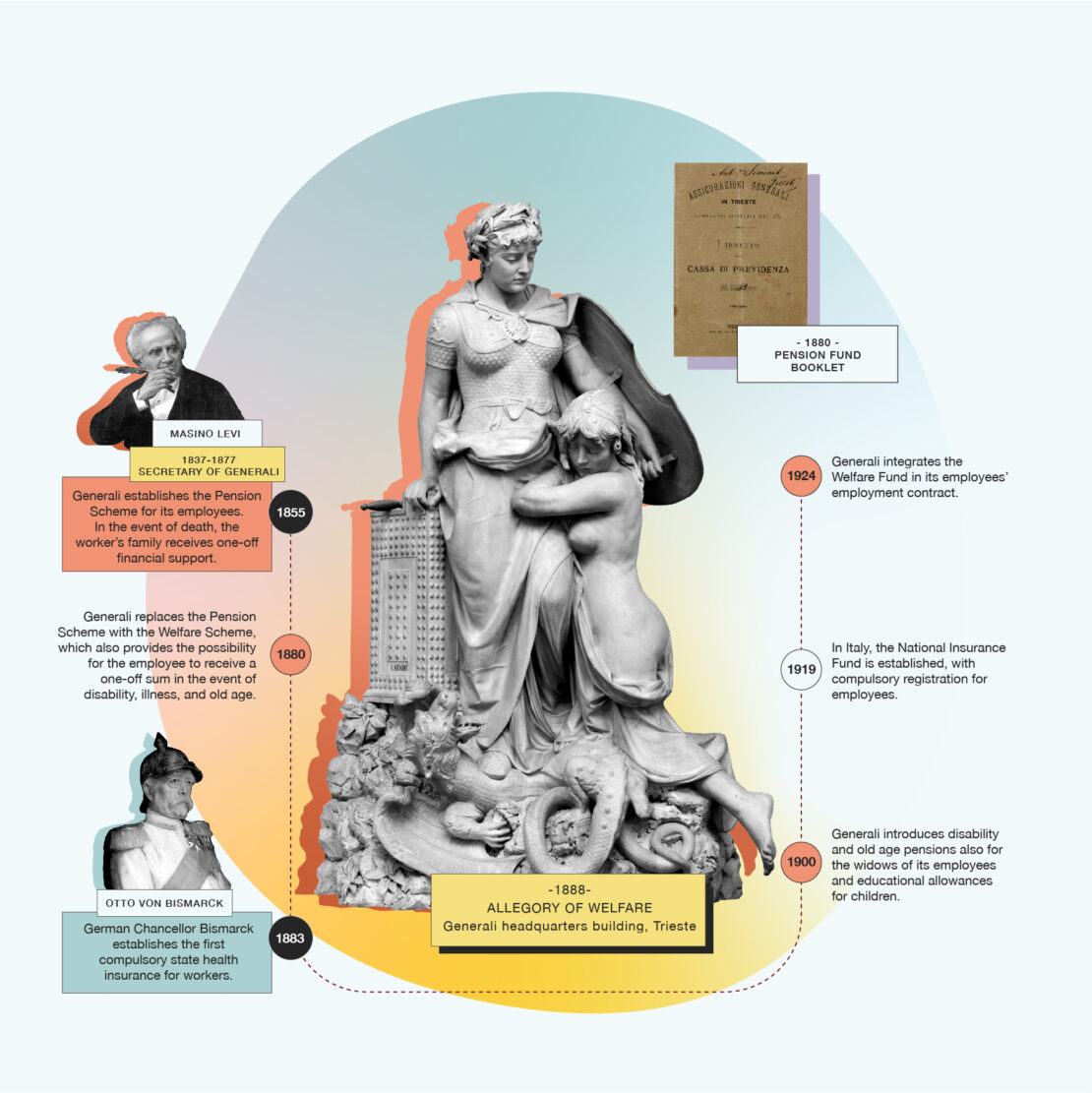

In January 1859, the government of Victor Emmanuel, the last king of Sardinia and shortly thereafter the first king of Italy, presented a bill for the establishment of a Pension Fund for elderly workers to the Piedmont parliament. In Germany, in 1883, Otto von Bismarck introduced health insurance. The German state followed it with accident insurance in 1884 and old age insurance in 1889. Italy followed a few years later, establishing the National Insurance Fund for the disability and old age of workers in 1898, made compulsory in 1919.

Generali had moved well in advance of state governments. The company cultivated ingenious ideas, aimed at activating plans for the future of its employees. Already in 1853 and 1854, thanks to the foresight of the secretary general Masino Levi, the “Pension Scheme” was born, designed to provide for families in the event of the death of employees. In 1877, Levi handed over to Marco Besso, a true innovator in the life insurance sector, who succeeded him in the role of secretary general.

Besso identified some problems: the financial insufficiency, the accumulation of debt for future pensions as a result of the large number of members and contributions payable by the company. Therefore, he felt the need to strengthen the foundations of the system, making use of his experience and his studies in the field, acquired at national and international level. In those same years, he dedicated his actuarial expertise to a series of proposals on pension and mutual aid companies, which he considered one of the most genuine expressions of liberalism, of its vocation to individual fulfilment. In 1880, Generali therefore established the “Welfare Scheme”, which included, in addition to the case of death, also those of disability and old age. In 1923, it dissolved the “Welfare Scheme” and established the “Welfare Fund”, which became an integral part of the collective employment agreement for the staff of the Italian Management.

The repercussions were considerable, for the employees and for the company itself. The Pension Scheme, then Welfare Scheme, and finally Welfare Fund, actively involved the workers and their families, offering them valuable support in times of difficulty. At the same time, it increased employees’ sense of belonging and their loyalty to the company.

But the action of the Pension Scheme wasn’t limited to creating mutual benefit for workers and company alike. In fact, it also included an idea of corporate welfare ahead of its time and not common in other professional companies of the day. The fact that employees, in addition to a safe workplace, could count on guarantees for their own health and old age, as well as that of their families, was an element of social distinction. And the affection for the company had a positive influence on society in general.

A careful reading of the data can give an idea of how much the Pension Scheme changed the life horizons of Generali’s people.

The financial statements related to 1855 are the first to detail the state of the Pension Scheme. In the first year of activity, with 1,276 employees, there were 4,942.17 florins in cash. In 1866, the year of Veneto’s passage to Italy, the Pension Scheme was in possession of 131,405.33 lire, equal to the total of the silver coin put into circulation in the Kingdom of Italy. In 1881, fifty years after the birth of Generali, there were 6,135 employees, including inspectors and agents, and the fund rose to 484,566.22 lire. In 1906, at Generali’s 75th anniversary, there were 15,562 employees and 1,092 members, while the Welfare Scheme’s fund reached 5,543,811.11 lire and grew steadily, despite a slight decrease after the First World War.

This constant and consistent growth was the sign of a shared hope, which spread throughout society from the company and its employees. As Marco Besso concluded on the 24th of February 1910, at the end of a conference held at the Roman college: “Utopia will become the reality, and all of our most daring will be true, alive, and palpable […] if to a human and wise work of distribution of new and ever increasing our material resources, you will be able to couple a no less wise and human distribution of the risks that are inseparable from our existence, causing such a small fraction to fall on the individual, as to make them easily bearable to everyone.”