From Game of Thrones to Trieste: a precious Seneca manuscript of the Generali Heritage

28 March 2024

The Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium (Moral Letters to Lucilius) is a collection of 124 letters divided into several volumes (the distribution varies, mostly 20-22 volumes) written between 62 and 65 AD, in the final years of his life, by the Cordoba-born Latin philosopher and writer Lucius Anneus Seneca (4 BC – AD 65) to his friend Lucilius Iunior, a poet, writer, and governor of Sicily.

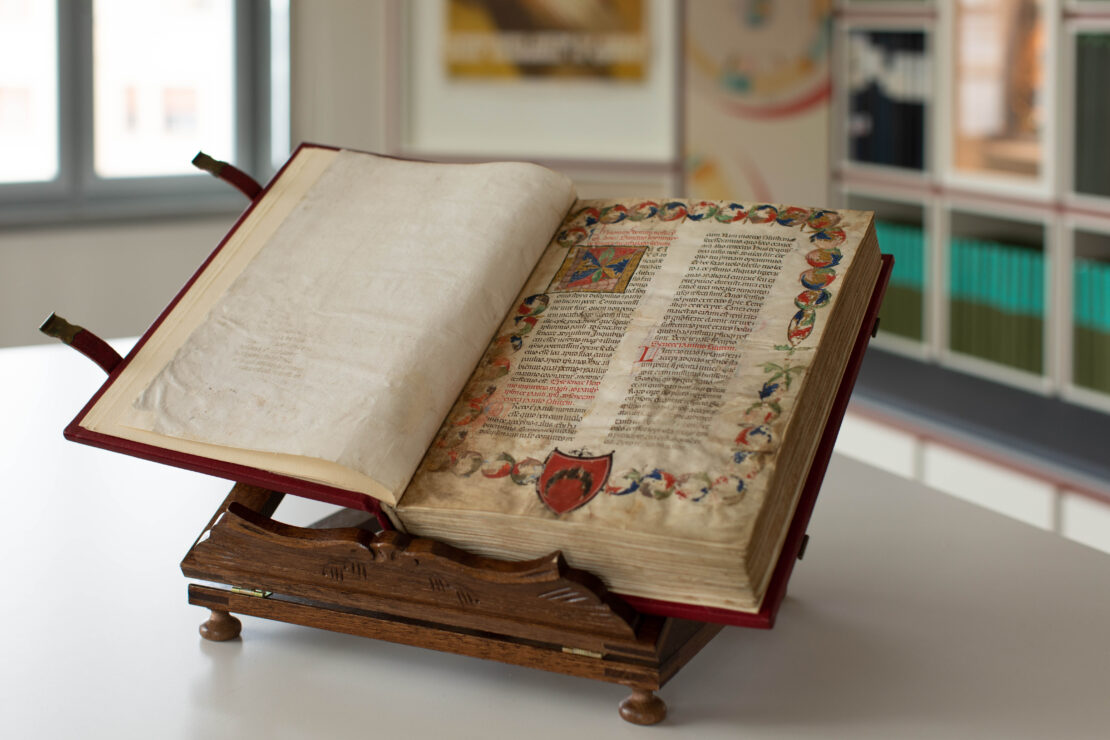

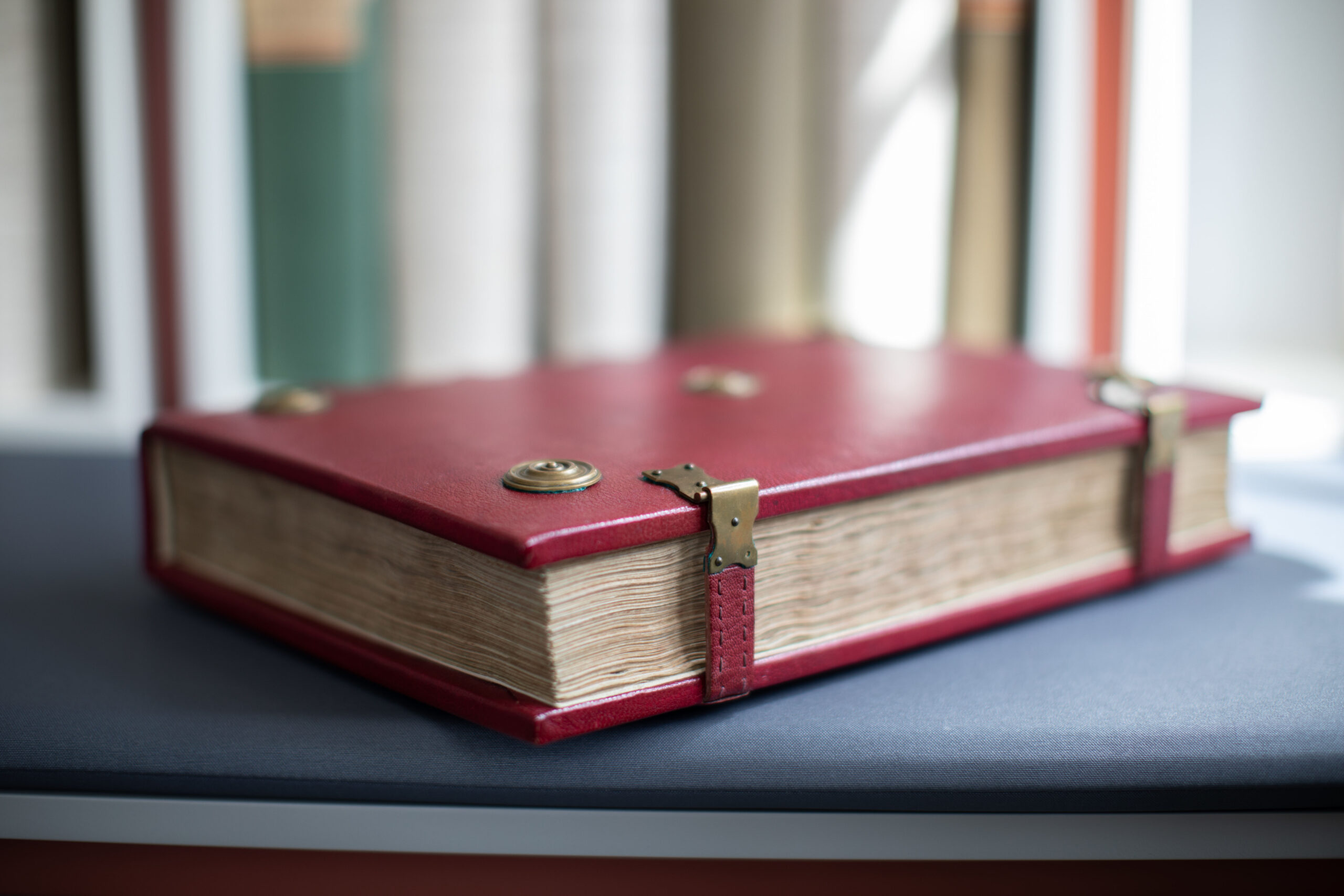

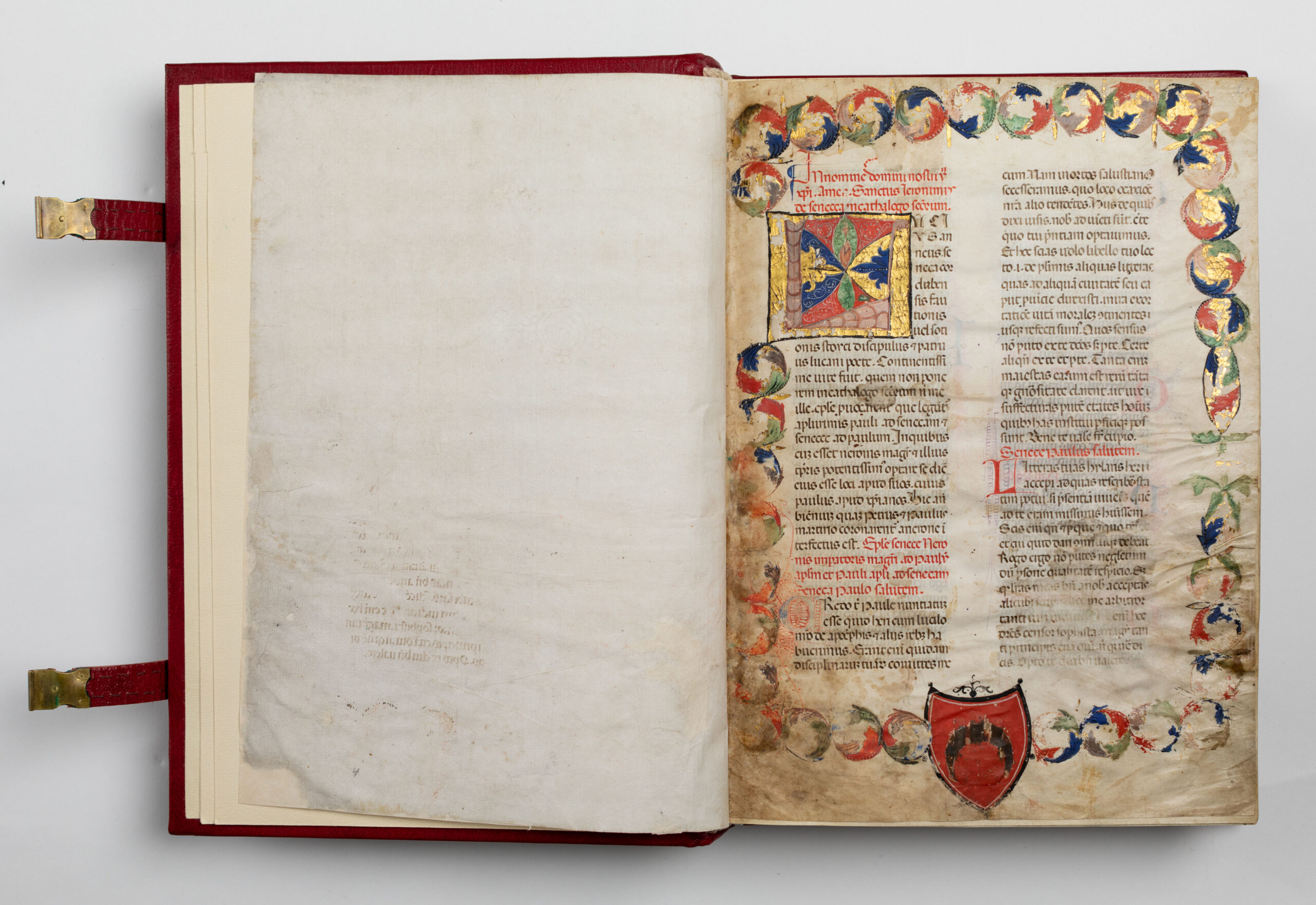

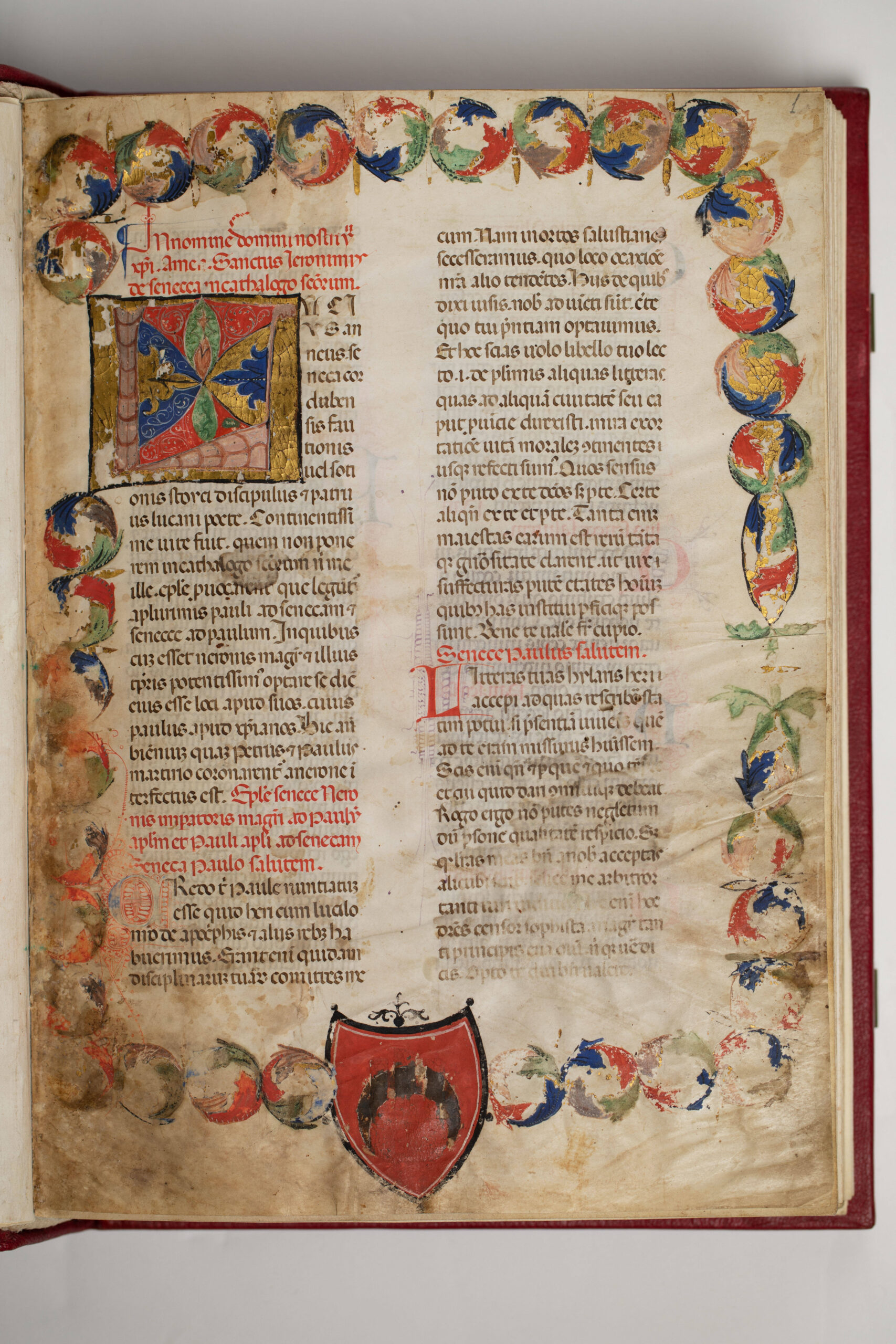

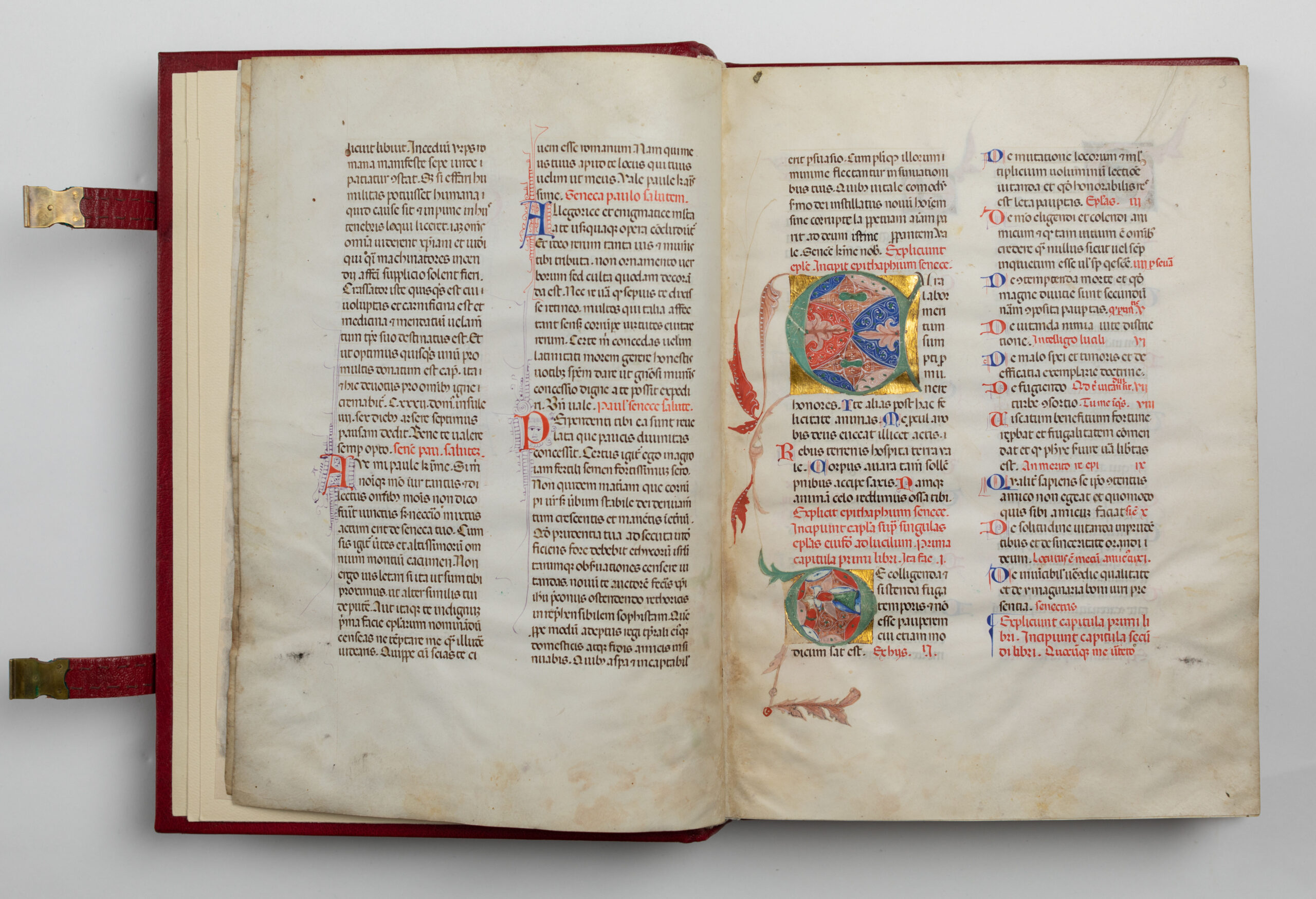

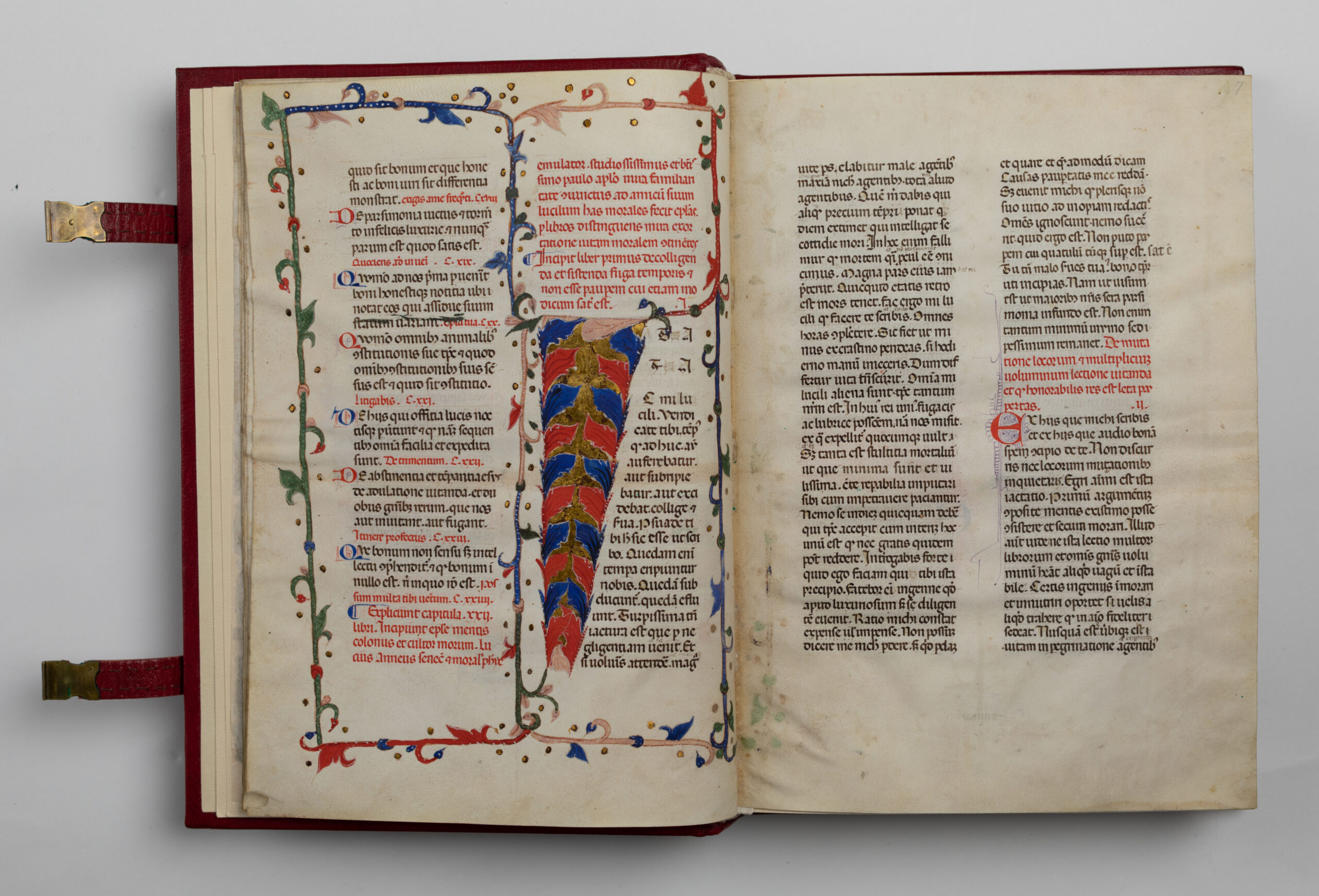

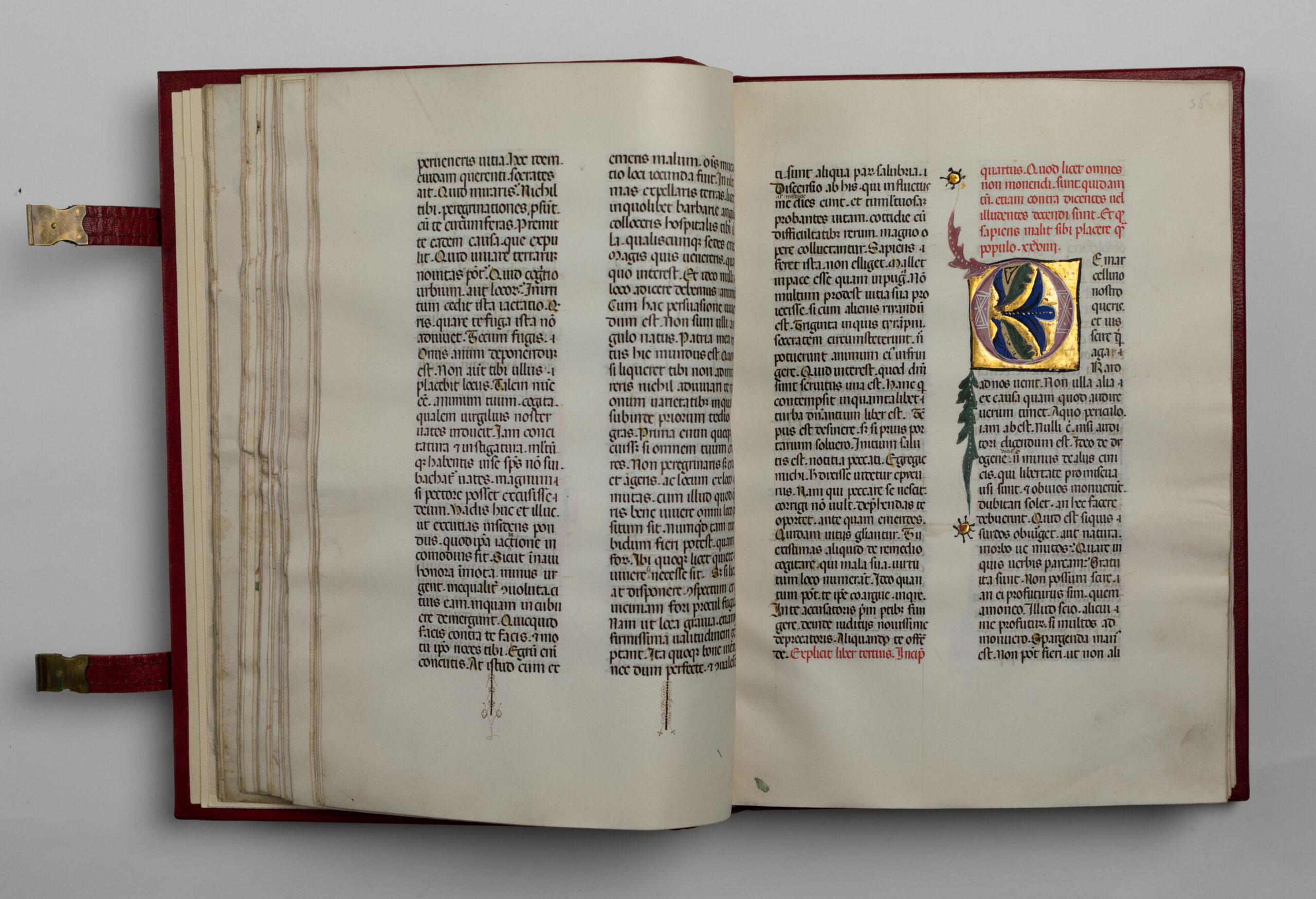

The manuscript, on parchment and in Gothic script, entered the Generali heritage in 1956, through a resolution on 12 June by Banco Vitalicio of Madrid, which chose to celebrate Generali’s 125th anniversary with this precious gift to the Board. It was not chosen randomly, but carried an important symbolism, since nothing represents the spirit and identity of Spain like Seneca. The coat of arms on the first page, an inverted crescent moon on a red background, connects the manuscript with the noble De Luna of Aragon family, an ancient Spanish lineage named for its possession of the city of Luna in the province of Zaragoza. The antipope Benedict XIII (1328-1423) was of this family, and its seaside castle in Peñíscola (Valencia) still bears this insignia on the entrance door.

The philologist Roberto Benedetti has carried out an in-depth investigation of the manuscript to date it, place it in a geographical context, and above all reconstruct its ownership history. In acknowledgement of its preciousness, he judges it ‘beyond doubt one of the most important manuscript testimonies preserved in Trieste, alongside the most significant codices of the Petrarchesco Piccolomineo Museum in the “Attilio Hortis” civic library’.

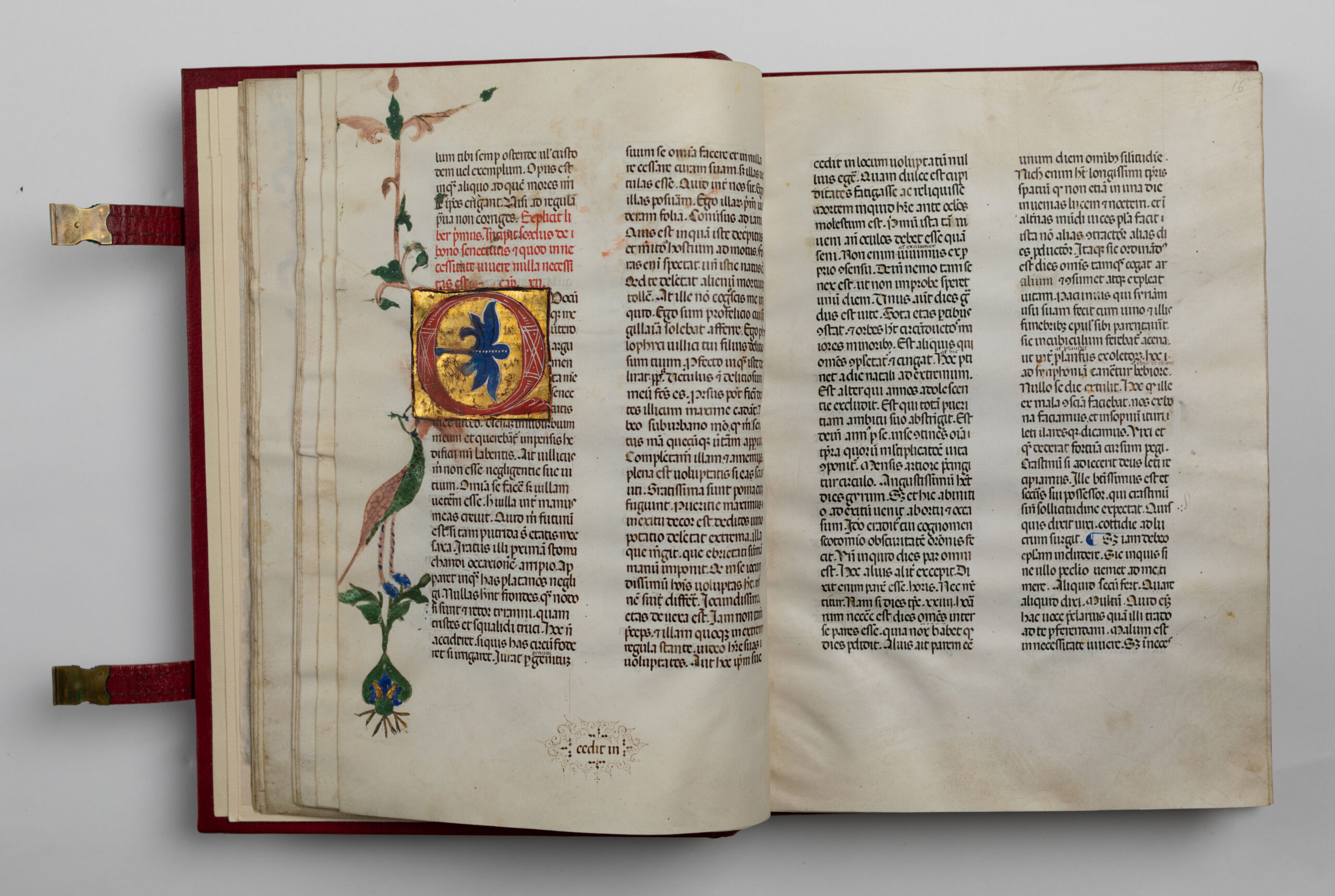

This precious codex was probably created to be donated, perhaps to strengthen some alliance. The quality of the assembled texts and certain iconographic details suggest a creator of considerable intellectual stature. An important detail to note is the progressive rethinking: designed to be donated, it was then destined to remain the property of the possessor or commissioner. In fact, the coat of arms on the home page appears to be superimposed on a primitive shield. It depicts a castle with three crenellated towers, the middle one windowed and a little taller than those on either side, perhaps a reference to both Castilian and Aragonese royal residences. Benedict XIII played a fundamental role in the succession to the Spanish throne, supporting the coronation of Ferdinand I of Aragon in 1412 and thus contributing to the birth of a dynasty that strengthened the links between the crowns of Castile and Aragon, anticipating the eventual union of the two Iberian crowns in a single political state. For political reasons, his successor, Alfonso V, known as “the Magnanimous”, was less supportive of Benedict, who was excommunicated and deposed in 1417 by a decree of the Council of Constance. Abandoned by all and with the troops of the hostile Alfonso V controlling him remotely, Benedict XIII spent the last years of his life confined to his Peñiscola residence. His sole consolation remained the precious and beloved volumes of his abundant library, which probably included this codex, where he created a scriptorium employing scribes and illuminators.

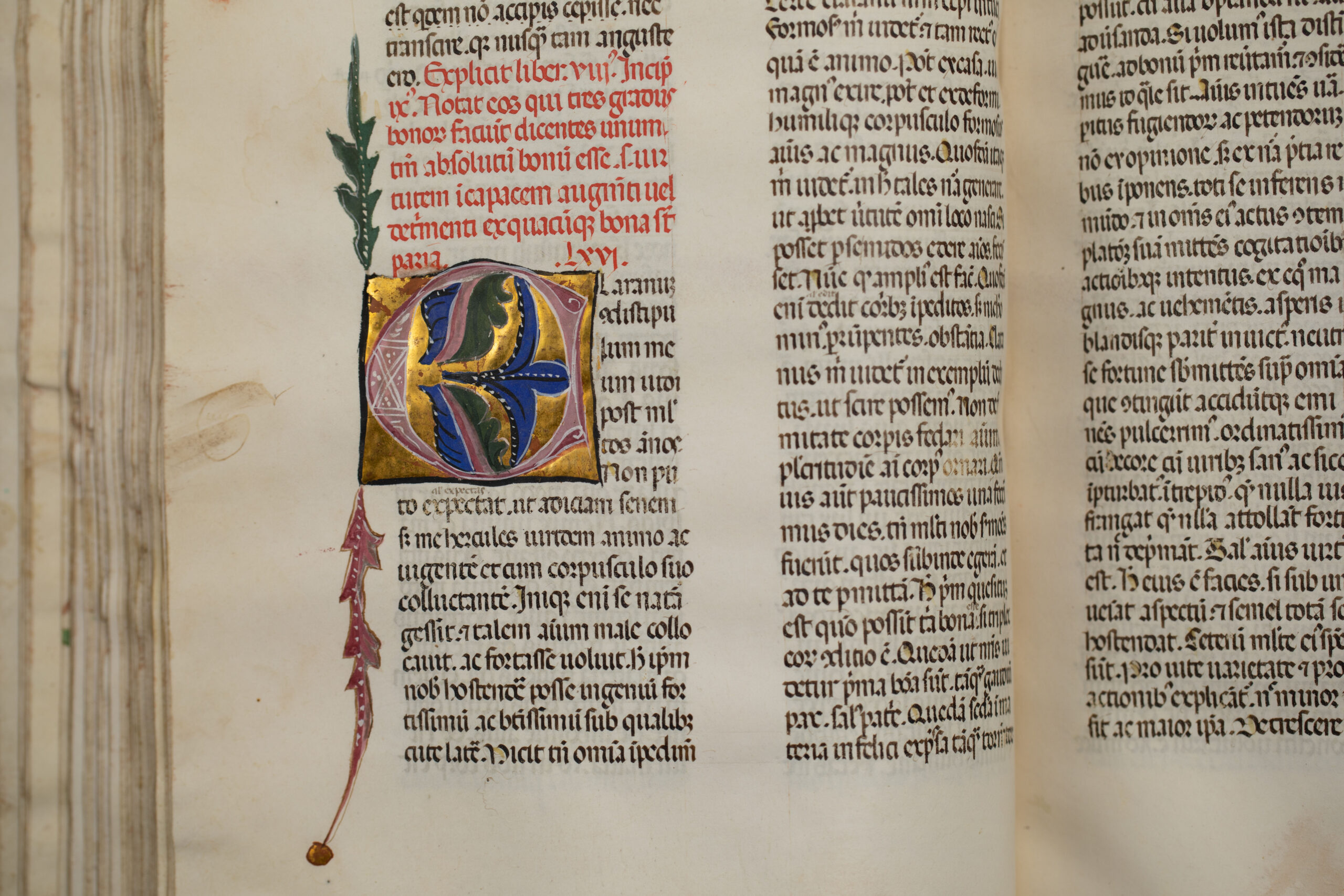

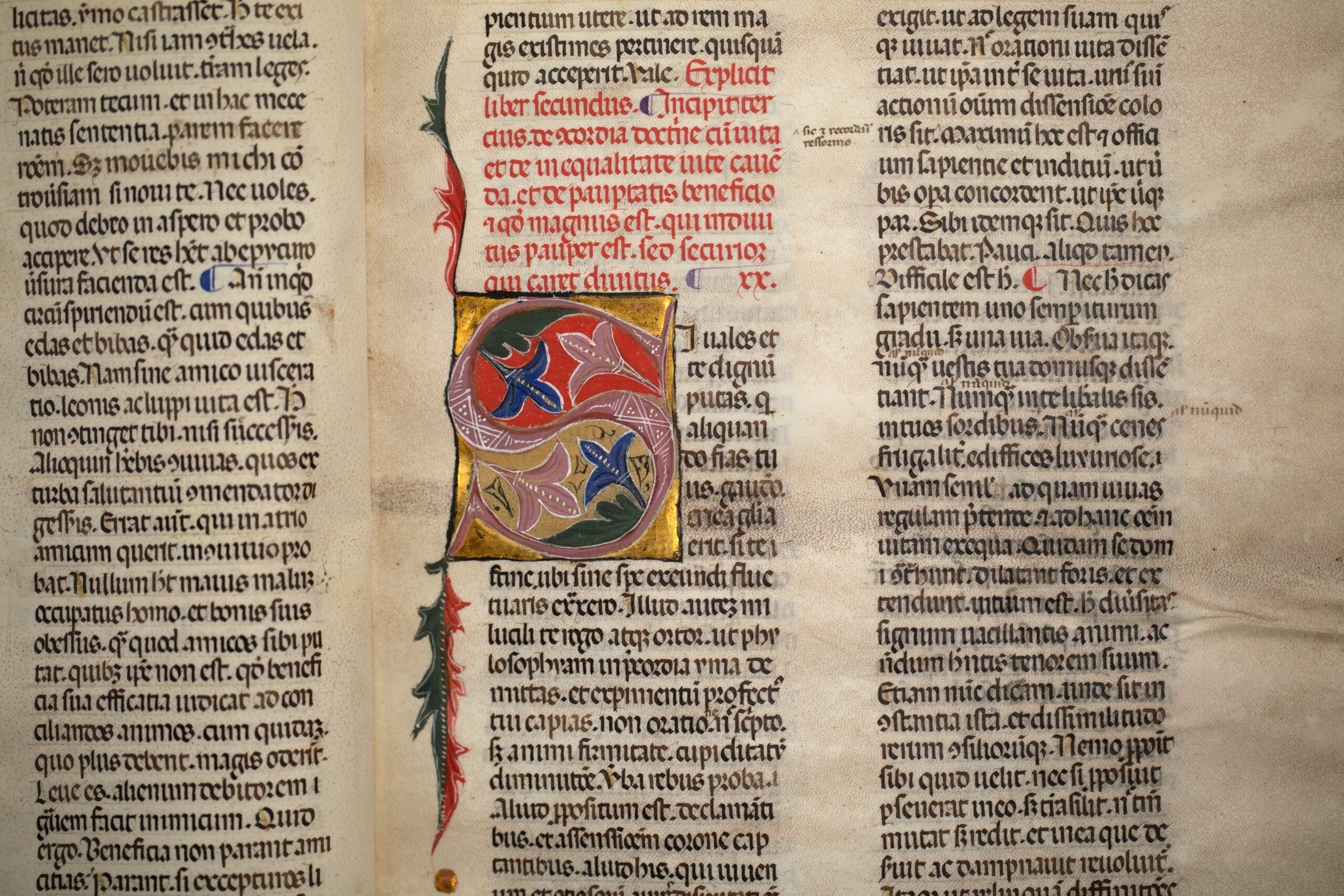

These historical and biographical premises, supported by iconographic references and glosses highlighting passages of the text that reveal the writer’s political views and thoughts, indicate that they were not written by other members of the de Luna family. They confirm the hypothesis of commission/ownership by the antipope Benedict XIII, the circumstances of its creation (the succession to the Spanish throne), the change of heart (the hostility of Alfonso V), the terminus ante quem (1416), and above all the particular feature of the codex that makes letter number 102, with its predominant theme of death and the afterlife, unique. Its transposition of the predominant theme of death and the afterlife from a sequential position to the conclusion of the work, “suggests that the manuscript was commissioned by a highly cultured bibliophile who wished to convey an edifying message with the book structured in this form, perhaps to an elderly recipient or to someone who had recently suffered a bereavement, given the prominence of the reflection on death at the end of the book.”

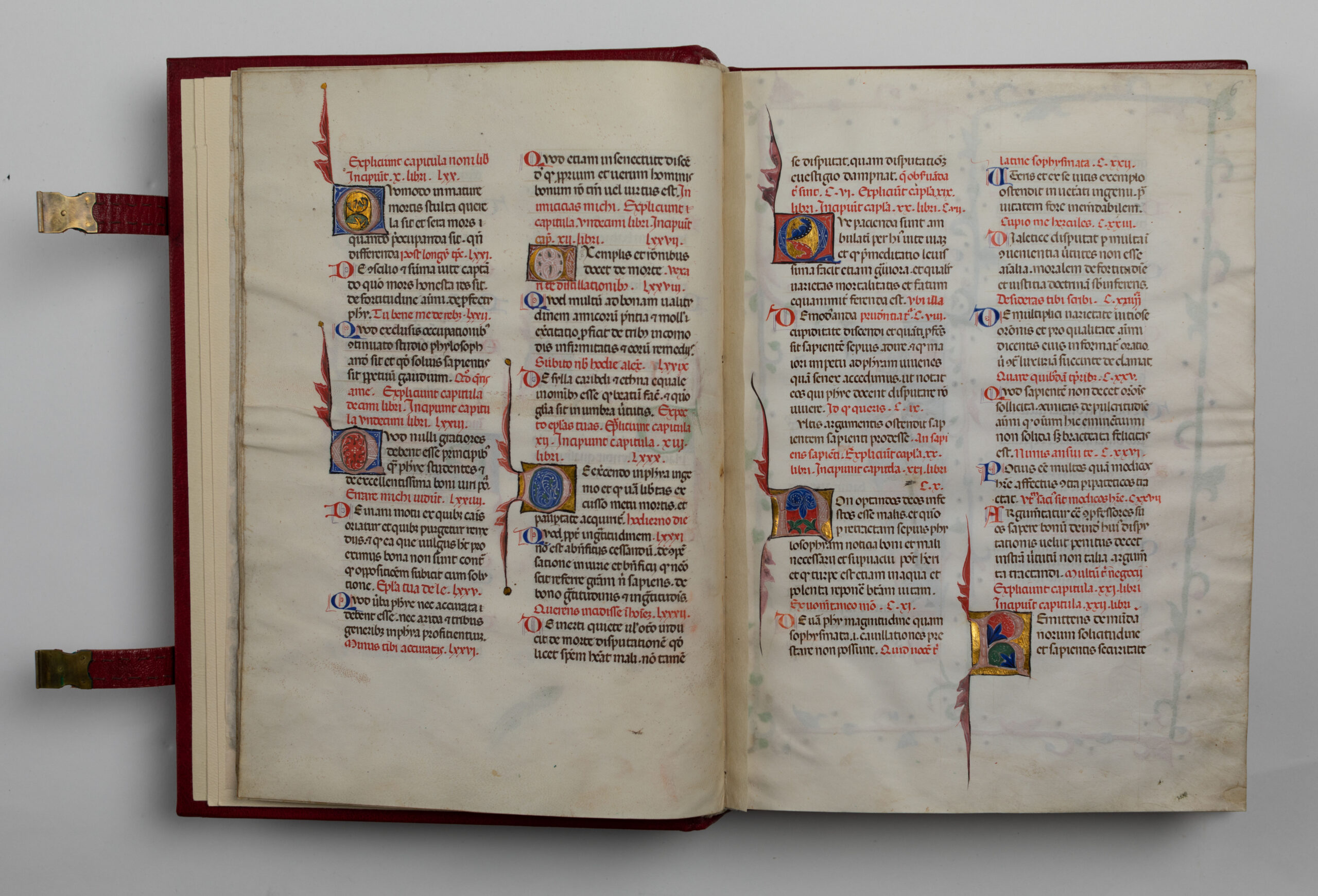

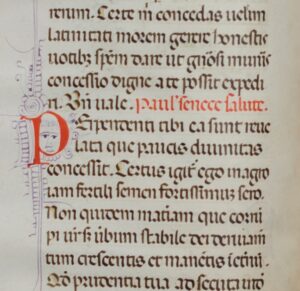

The intrinsic characteristics of the text also place it in the Catalan region, with a style that can be defined as Italo-Gothic and which is evident in the use of drollery: small faces at the end of chapters or as fillers in illuminated letters, an ornamental and emotional device that creates empathy between reader and scribe.

The precious library was probably dispersed after the death of Benedict XIII by his successor Clement VIII, eager to free himself from a legacy that was now politically inconvenient and to make easy money by selling the most valuable volumes. In fact, the inventory of the library drawn up after his death in 1423, lists a manuscript that seems to be recognisable as that of Generali. It would be interesting to compare it with later versions of the same inventory, reduced to about a third of the original size, to confirm the genesis of its introduction into the sales circuit of ancient codices.

After a long journey of almost five centuries, from the shores of Peñíscola, where Benedict XIII’s castle-fortress – the film set of Meereen in the medieval fantasy Game of Thrones – still stands, to the gulf of Trieste, Seneca’s manuscript now finds a safe haven at the historical headquarters building of Generali.